Butterfuss et al. (2020) discuss reading comprehension in relation to cognition, emotion, and learning. Key to reading comprehension is the creation of a mental representation of the information presented in the text (Kintsch 1988, as cited in Buterfuss et al 2020). To put it in a more formal light, reading comprehension is “the process of simultaneously extracting and constructing meaning through interaction and involvement with written language” (Snow, 2002, p. 11).

Challenges Today

Middle and high school students often face significant challenges with reading comprehension, which can hinder their academic success across subjects. Vocabulary gaps make it difficult for students to understand complex texts, especially in subjects like science and history, where technical terms are common. Additionally, a lack of background knowledge can prevent students from making meaningful connections to the text, leading to surface-level understanding rather than deep comprehension. Many students also struggle with analyzing texts, particularly when asked to identify themes, evaluate arguments, or infer meaning beyond what is explicitly stated. Without explicit instruction in critical reading strategies, students may rely too heavily on literal interpretation, missing the nuances that lead to deeper comprehension and engagement with the material.

Practical Strategies for Improving Students’ Reading Comprehension Skills

1. Build Background Knowledge

Background knowledge is essential for reading comprehension because it helps readers make connections, infer meaning, and retain information. Research shows that students with strong prior knowledge about a topic understand and recall text better, regardless of their reading ability (Recht & Leslie, 1988). Without relevant knowledge, readers struggle to interpret context, recognize key ideas, and differentiate important details from irrelevant ones. This is especially critical for complex academic texts, where unfamiliar vocabulary and abstract concepts can hinder understanding. Activating prior knowledge before reading enhances comprehension by providing a mental framework for integrating new information.

Here are 5 Steps to Leveraging Background Knowledge in Lessons:

- Find out what students already know

- Fill in necessary contextual pieces

- Empower kids to share what they know with their peers

- Facilitate connections between students’ experience and prior knowledge

- Provide activities and tasks that don’t rely on context

2. Teach Active Reading Strategies

Active reading strategies are various processes that good readers use before, during and after reading a text to make sure they have achieved comprehension of what they are reading. By actively working towards enhancing their comprehension skills, students can improve their reading speed while also increasing retention of information read (Teaching Assistants’ Training Program, 2025).

Here are some active reading strategies from The McGraw Centre for Teaching and Learning:

- Ask yourself pre-reading questions.

- Identify and define any unfamiliar terms.

- Bracket the main idea or thesis of the reading, and put an asterisk next to it.

- Put down your highlighter. Make marginal notes or comments instead.

- Write questions in the margins, and then answer the questions in a reading journal or on a separate piece of paper.

- Make outlines, flow charts, or diagrams that help you to map and to understand ideas visually.

- Read each paragraph carefully and then determine “what it says” and “what it does.” Answer “what it says” in only one sentence.

- Write a summary of an essay or chapter in your own words.

- Write your own test question based on the reading.

- Teach what you have learned to someone else.

3. Explicitly Teach Vocabulary in Context

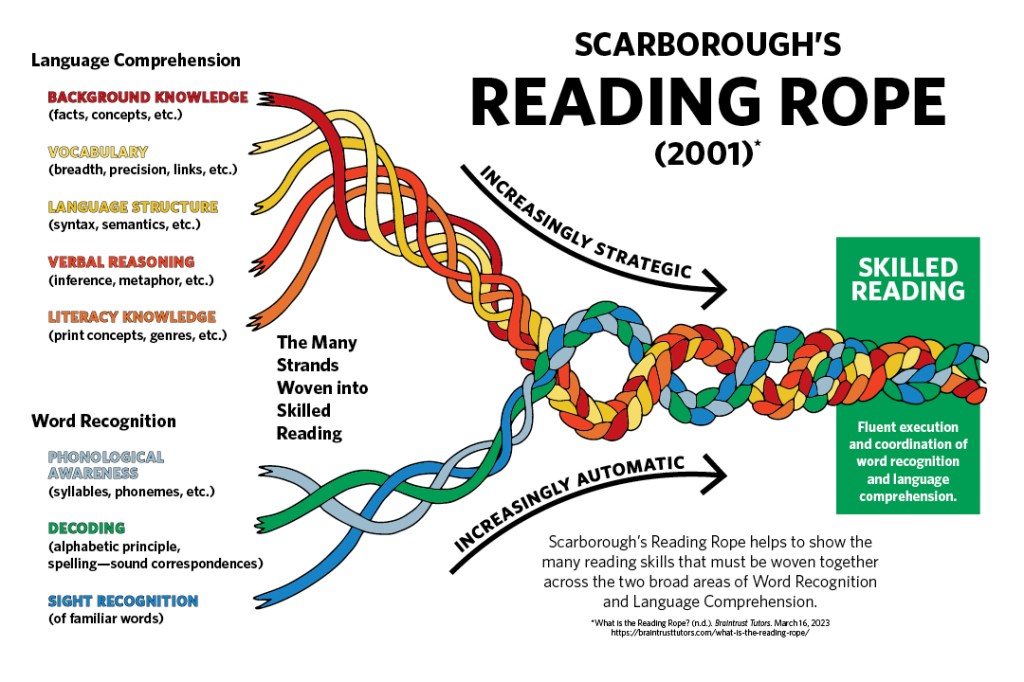

Scarborough’s Reading Rope (2001) highlights that skilled reading requires the integration of word recognition and language comprehension. Vocabulary is a crucial component of the language comprehension strand, directly influencing a reader’s ability to understand and interpret text. Without a strong vocabulary, students struggle to make meaning, even if they can decode words accurately. Explicit vocabulary instruction is essential because it helps students connect new words to prior knowledge, enhances their ability to infer meaning, and supports comprehension across subjects. Teaching vocabulary systematically ensures that students develop the language skills necessary for fluent and meaningful reading.

Using the Frayer Model to Explicitly Teach Vocabulary

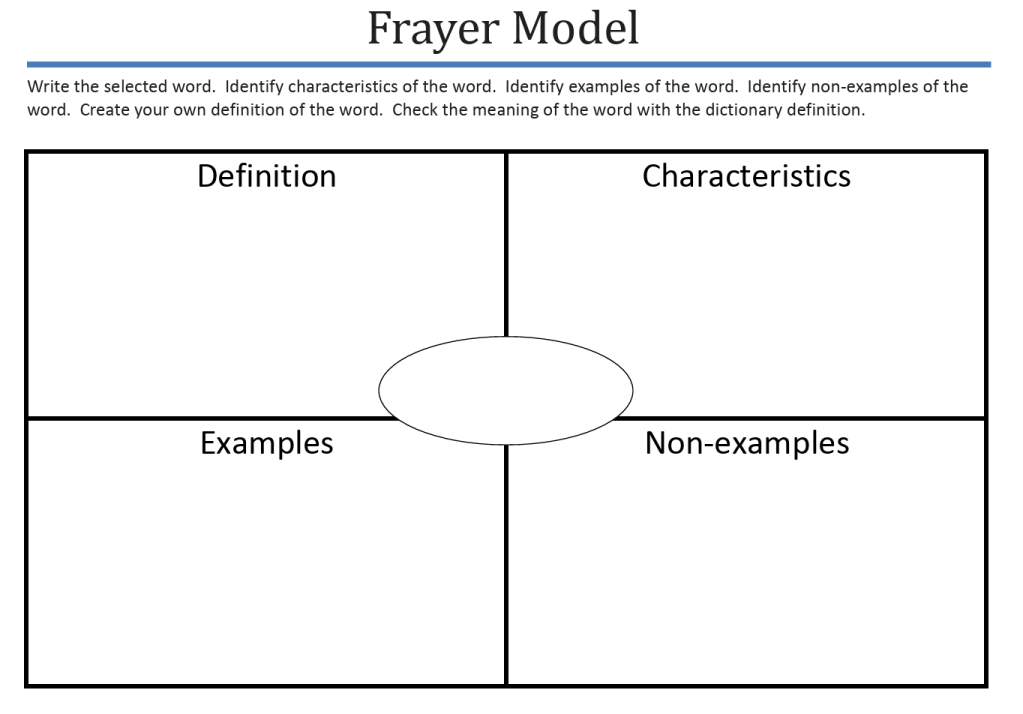

The Frayer Model is a graphic organizer that helps students define, analyze, and apply vocabulary words by breaking them down into four categories: definition, characteristics, examples, and non-examples.

1. Select a Vocabulary Word

- Choose a word from the text students are reading.

- Focus on a key concept essential for comprehension.

2. Introduce the Purpose of the Frayer Model

- Explain that this strategy helps clarify word meanings and builds connections between concepts.

- Let students know they will analyze the word’s definition, characteristics, examples, and non-examples.

3. Model the Process (Think-Aloud)

- Provide students with a blank Frayer Model.

- Demonstrate how to complete each section:

- Write the word in the center.

- Definition: Students write a student-friendly definition (scaffold if needed).

- Characteristics: List key features of the word.

- Examples: Provide real-world examples.

- Non-examples: List unrelated words or concepts to clarify meaning.

- Compare with a dictionary definition for accuracy.

4. Guided Practice

- Assign a vocabulary word to students.

- Have them complete the Frayer Model in pairs, small groups, or individually.

- Provide scaffolding where necessary.

5. Discussion and Application

- Use discussion to deepen understanding and clarify misconceptions.

- Have students share their Frayer Models with the class.

Conclusion

Effective reading comprehension instruction requires a multifaceted approach that combines background knowledge, active reading strategies, and explicit vocabulary instruction. Research has consistently shown that comprehension is not just about decoding words but about constructing meaning through interaction with text.

By incorporating strategies such as building background knowledge, engaging students in active reading, and using structured vocabulary models like the Frayer Model, educators can equip students with the skills they need to become strong, independent readers. Ultimately, fostering deep comprehension skills enhances academic success and lifelong literacy, ensuring that students are prepared to navigate complex texts in both school and beyond.

Share your thoughts! How do you currently teach reading comprehension? What’s one strategy you could implement right away to enhance student understanding?

References

Butterfuss, R., Kim, J., & Kendeou, P. (2020). Reading comprehension. In Oxford research encyclopedia of education. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.86

McGraw Center for Teaching and Learning. (n.d.). Active reading strategies: Remember and analyze what you read. Princeton University. Retrieved from https://mcgraw.princeton.edu/undergraduates/resources/resource-library/active-reading-strategies

Plotinsky, M. (2024, October 9). 5 steps to leveraging background knowledge in lessons. Edutopia. Retrieved from https://www.edutopia.org/article/providing-background-knowledge/

Recht, D. R., & Leslie, L. (1988). Effect of prior knowledge on good and poor readers’ memory of text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(1), 16–20. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.80.1.16

Rholetter, W. (2024). Reading comprehension. In Salem Press Encyclopedia, Research Starters. Salem Press. Retrieved from https://research.ebsco.com/c/sxhhzk/viewer/html/4k7wk5bixn

Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. In S. B. Neuman & D. K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research (Vol. 1, pp. 97–110). Guilford Press.

Snow, C. (2002). Reading for understanding: Toward an R&D program in reading compre hension. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation.

Teaching Assistants’ Training Program. (2025). Active reading strategies. University of Toronto. Retrieved from https://tatp.utoronto.ca/resources/active-reading-strategies/

Leave a reply to John J Horrigan Cancel reply