I watched Mia squint at her paper.

It was the third period on a Tuesday morning. My Grade 9 students were working on a short reading comprehension task. Mia, usually confident and articulate in discussions, had frozen. The question was straightforward: “Evaluate the author’s perspective.” But after five minutes, her page remained blank.

Later, when I checked in, she said something that stuck with me:

“I know what the author said. I just don’t know how to explain if I agree or not… or why.”

Mia could summarize. She could identify key vocabulary. But when it came to analyzing an argument or evaluating its credibility, she stalled. It wasn’t that she couldn’t read. It was that she hadn’t yet learned to read critically.

The Theory: Anderson and Krathwohl’s Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy

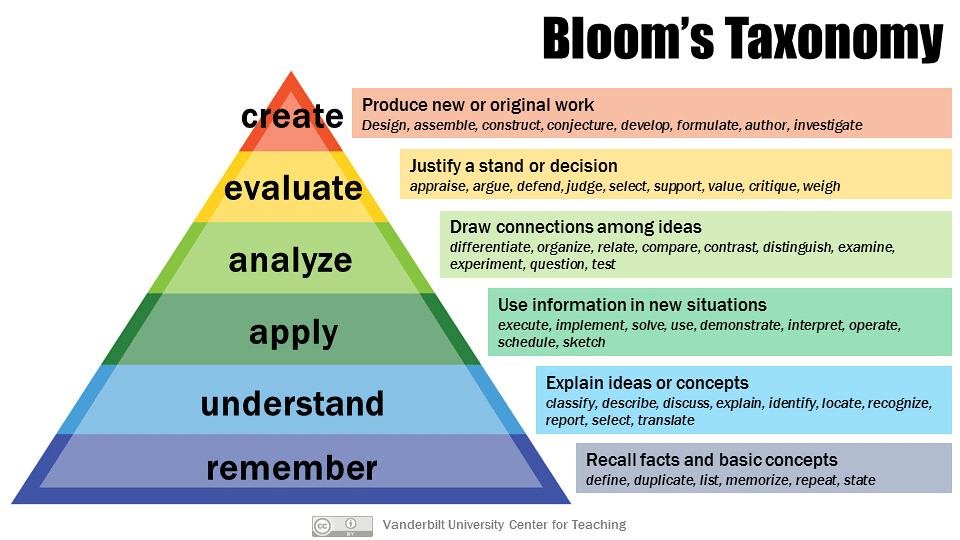

In 2001, Anderson and Krathwohl revised Bloom’s famous taxonomy of cognitive skills. They offered a more dynamic view of how students learn.

Students often spend much of their school life operating in the lower three levels. However, success in higher education – and life – demands skill in the upper tiers: analyzing, evaluating, and creating. This is especially true when it comes to reading critically.

The Challenge: A Gap Between Perception and Performance

A recent study by Rosalyn G. Mirasol (2024) involving over 600 junior high school students in the Philippines revealed a surprising trend. Students believed they were skilled at using critical reading strategies. They rated themselves highly on tasks such as predicting outcomes, evaluating arguments, and synthesizing ideas.

But their reading test results told a different story.

Across the board, students performed well in knowledge-level tasks (e.g., identifying the title or finding literal information), but struggled in higher-order tasks like synthesis and evaluation.

It’s a sobering reminder: students often don’t know what they don’t know.

The Solution: Make Critical Reading Strategies Explicit

So how can we bridge the gap between perception and performance?

Here are a few classroom-tested strategies, backed by research:

1. Teach the Taxonomy

- Introduce students to the six cognitive processes.

- Use color-coded posters or bookmarks to help them identify question types (“Is this a comprehension question or an evaluation?”).

- Let them practice writing their own questions at different levels.

2. Model Metacognition

- Think aloud while annotating a text. Show how you question assumptions, connect ideas, and assess evidence.

- Highlight when you’re operating in a specific cognitive domain (“Right now I’m analyzing because I’m comparing these two viewpoints”).

3. Use Rich, Varied Texts

- Go beyond traditional print: include editorials, infographics, social media posts, and opinion articles.

- Challenge students to examine why the text was written and how it influences the reader.

4. Integrate sentence stems to scaffold higher-order thinking.

- Provide students with sentence starters tailored to each cognitive level—for example,

- “The author’s main argument is…” (Understanding)

- “This idea connects to…” (Applying)

- “The evidence is strong/weak because…” (Evaluating)

- “Combining these ideas suggests that…” (Synthesizing)

- This approach helps students internalize academic language while gradually building confidence in articulating complex thoughts.

5. Incorporate Non-Cognitive Assessments

- Use surveys to gauge reading motivation, confidence, and attitudes.

- Discuss mindset and the value of persistence in tackling complex texts.

The Takeaway: Knowing Isn’t Enough

As teachers, we often assume students can engage critically because they can summarize or decode. But as Mia’s pause reminded me—there’s a world of difference between reading and reading deeply.

We must move beyond surface-level tasks. This is crucial to prepare students for the complex demands of tertiary education. Additionally, this helps them navigate a world flooded with misinformation. We need to teach them how to think about how they think. Critical reading isn’t just about understanding a text. It’s about understanding the world—and their place in it.

References

Mirasol, R. G. (2024). Exploring junior high school students’ critical reading strategies and reading performance. Cogent Education, 11(1), Article 2416814. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2024.2416814

Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board. (2025). Revised Bloom’s taxonomy. OERTX. https://oertx.highered.texas.gov/courseware/lesson/1548/student/?section=8

Join the Conversation

How do you help your students move beyond surface-level reading? Have you noticed a gap between what they think they can do and what they actually demonstrate? I’d love to hear your experiences, strategies, or questions. Let’s keep learning together. #ResearchForTeachers #CriticalReading #LiteracyMatters

Leave a comment