Imagine you’re teaching Frankenstein in Baghdad by Ahmed Saadawi, an Arabic retelling of Mary Shelley’s classic, to a group of secondary students. Some students immediately grasp the novel’s deeper themes of justice, revenge, and the consequences of war. Others struggle, unable to contextualize the chaotic post-war Baghdad setting. You pause and ask, “What do you know about the Iraq War and its political fallout?” A few hands shoot up, discussing the US invasion, sectarian violence, and the instability that followed. Others remain silent. It quickly becomes clear—those with prior historical and political knowledge engage with the novel effortlessly, while those without struggle to interpret its meaning beyond the surface.

This classroom moment is a direct reflection of what research has confirmed for decades: background knowledge plays a critical role in reading comprehension.

The Challenge: Why Do Some Students Struggle with Reading Comprehension?

For years, the dominant approach to teaching reading comprehension has focused on generic strategies – summarizing, predicting, and questioning. While useful, these strategies alone are not enough to bridge comprehension gaps.

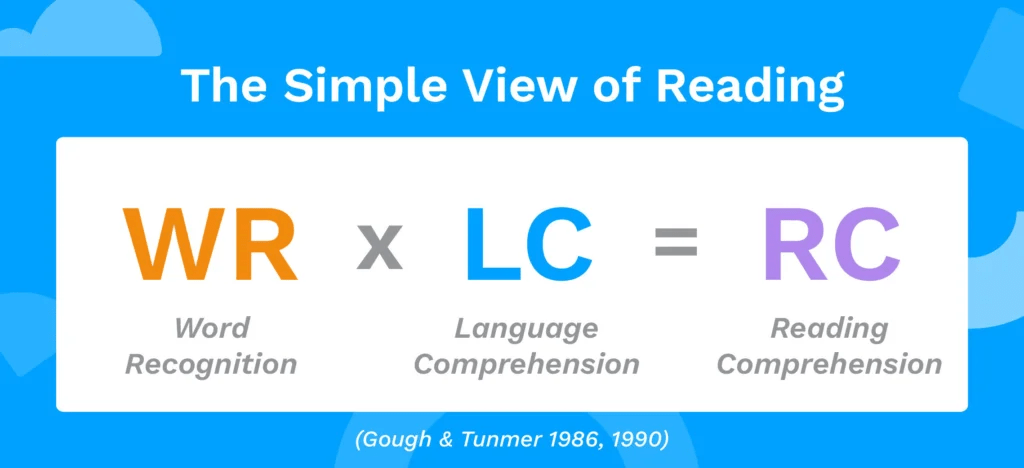

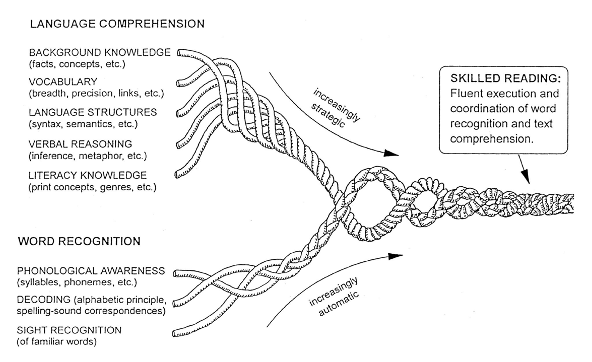

The Simple View of Reading (Gough & Tunmer, 1986) posits that reading comprehension is the product of decoding and language comprehension. However, more recent research highlights that comprehension is far more complex. Kintsch’s (1998) Construction-Integration model explains that readers construct meaning by integrating new information with what they already know. Without sufficient background knowledge, students struggle to form a coherent understanding of the text.

Studies support this. Recht & Leslie (1988) found that students with extensive baseball knowledge comprehended a passage about baseball far better than those with higher general reading ability but little knowledge of the sport. Similarly, McNamara et al. (1996) showed that students with limited background knowledge needed high-cohesion texts to understand content, while those with strong background knowledge thrived even with low-cohesion texts.

by H.S. Scarborough, 2001, in S.B. Neuman and D.K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of Early Literacy Research

(Vol. 1, p. 98), New York, NY: Guilford. Copyright 2001 by The Guilford

In short, comprehension isn’t just about skill – it’s about what students bring to the reading experience.

The Solution: Building a Knowledge-Rich Curriculum

So, how do we ensure that all students develop the background knowledge they need to comprehend complex texts?

1. Prioritize Knowledge-Building Over Isolated Reading Strategies

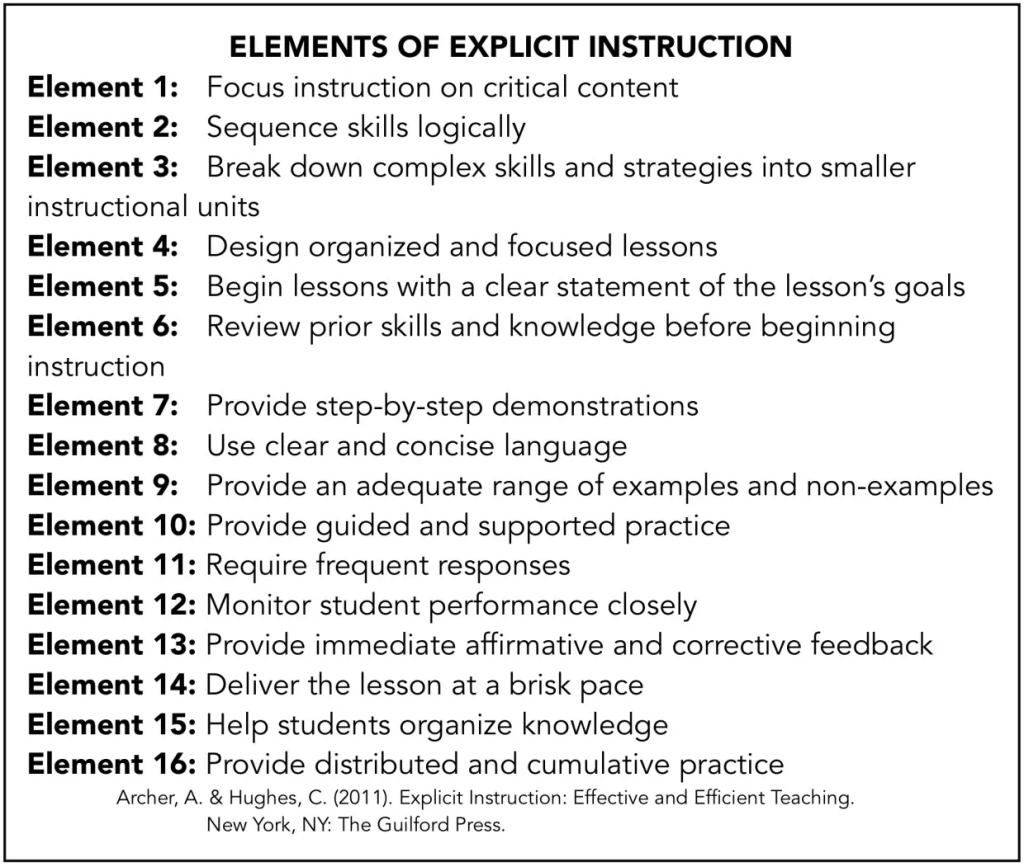

Instead of focusing solely on skills like “finding the main idea,” students should be immersed in content-rich instruction. Cervetti & Wright (2020) argue that explicit knowledge instruction is more effective than strategy-based comprehension lessons alone.

2. Scaffold for Struggling Readers

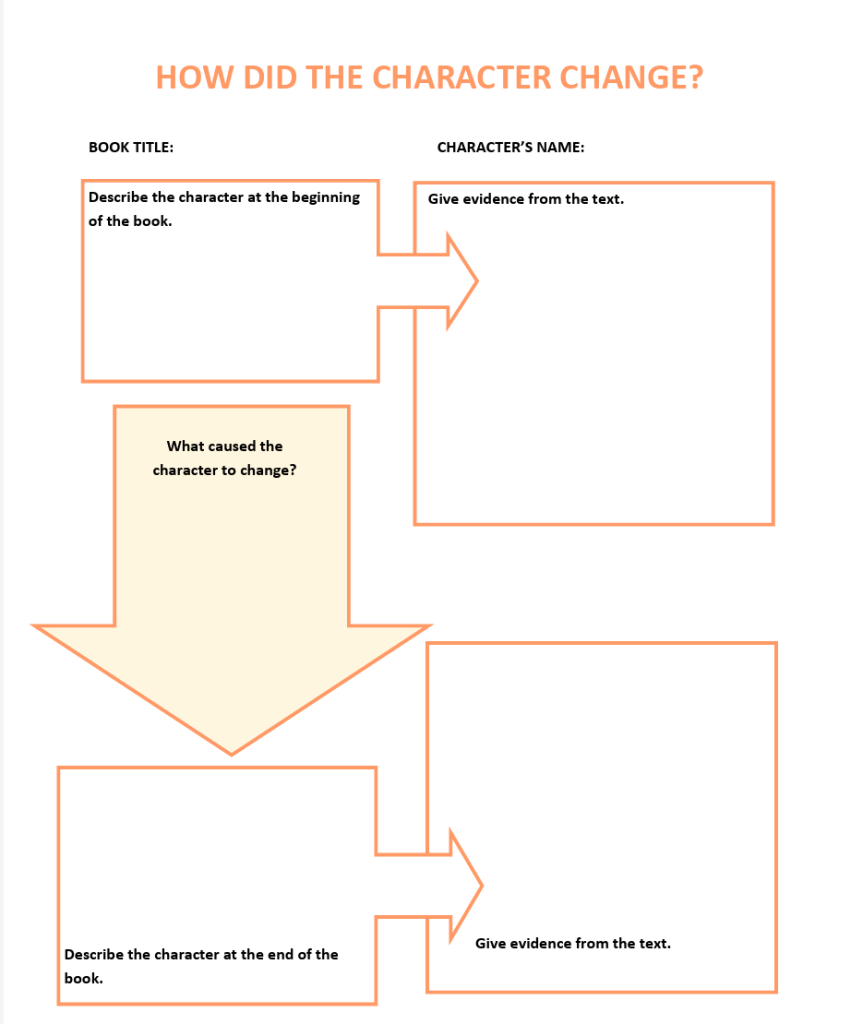

Not all students enter the classroom with equal knowledge. McKeown et al. (1992) found that weaker readers benefited most from high-cohesion texts that made connections explicit. Teachers can support comprehension by frontloading key concepts, using graphic organizers, and providing structured discussions to activate prior knowledge.

3. Address Misconceptions Directly

A challenge with background knowledge is that it can sometimes be incorrect. Lipson (1982) found that students often disregarded text information that contradicted their prior beliefs. Explicitly discussing and correcting misconceptions is essential for building accurate, usable knowledge. Conducting a “Fishbowl Discussion” is just one effective method.

Conclusion: Knowledge Is Power in Reading

The idea that “reading comprehension is about more than just words” is well-supported by decades of research. Background knowledge is not simply a helpful addition—it is a core component of understanding text. As educators, we must move beyond isolated strategy instruction and build knowledge systematically. This means integrating science, history, and rich literature into daily instruction, ensuring that all students have the foundational knowledge they need to engage deeply with text.

Next time a student says, “I don’t get it,” before jumping to a comprehension strategy, ask yourself: Do they have the background knowledge they need to understand this text?

The answer might be the key to unlocking their reading success.

References

Cervetti, G. N., & Wright, T. S. (2020). The role of knowledge in understanding and learning from text. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(S1), S1–S9. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.333

Gough, P. B., & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7(1), 6-10. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193258600700104

Kintsch, W. (1998). Comprehension: A paradigm for cognition. Cambridge University Press.

Lipson, M. Y. (1982). Learning new information from text: The role of prior knowledge and reading ability. Journal of Reading Behavior, 14(3), 243–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/10862968209547458

McKeown, M. G., Beck, I. L., Sinatra, G. M., & Loxterman, J. A. (1992). The contribution of prior knowledge and coherent text to comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 27(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.2307/747832

McNamara, D. S., Kintsch, E., Songer, N. B., & Kintsch, W. (1996). Are good texts always better? Interactions of text coherence, background knowledge, and levels of understanding in learning from text. Cognition and Instruction, 14(1), 1-43. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532690xci1401_1

Recht, D. R., & Leslie, L. (1988). Effects of prior knowledge on good and poor readers’ memory of text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(1), 16-20. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.80.1.16

Join the Conversation!

What are your thoughts on the role of background knowledge in reading comprehension? Have you noticed this challenge in your own classroom? Share your experiences, strategies, and insights in the comments below or on social media. Let’s build a knowledge-rich community together!

Leave a comment