A few days ago while teaching Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, I had a student who was completely frustrated with Victor’s narration. “Why doesn’t he just say what he means?” she asked, exasperated. We were analyzing one of his long, guilt-ridden monologues, where he wrestles with the consequences of creating life. Words like despondence, insurmountable, and ignominy left her stuck—not because she didn’t understand the story, but because she lacked the vocabulary to fully grasp Victor’s internal torment.

More than that, she hadn’t yet recognized how Mary Shelley, as a woman in the early 19th century, was crafting a narrative steeped in male hubris and unchecked ambition. Once we broke it down – paraphrased, connected it to modern anxieties about scientific ethics – her frustration shifted.

“Oh,” she said, “so he’s basically spiraling because he played God and now regrets it?” Exactly. And suddenly, she got why Shelley told the story the way she did.

What is the relationship between reading comprehension and vocabulary knowledge?

Reading comprehension and vocabulary are deeply interconnected. Wagner and Meros (2010) explain that vocabulary influences comprehension through direct, indirect, and reciprocal means. Directly, knowing word meanings enhances understanding; indirectly, vocabulary affects phonological awareness and decoding, which support comprehension.

Additionally, comprehension fosters vocabulary growth, as students learn new words through reading. Nation (2009) found that up to 10% of children aged 7–11 struggle with comprehension despite fluent decoding, often due to weak vocabulary knowledge. This reinforces the idea that vocabulary is a foundational element of reading comprehension, influencing inference-making, comprehension monitoring, and text engagement.

Digging Deeper into the Research

- Indirect Influence of Vocabulary on Comprehension – Vocabulary impacts reading comprehension indirectly through phonological awareness and decoding skills. Since phonological processing is essential for early reading development, students with a stronger vocabulary often have an advantage in decoding and overall reading fluency (Wagner and Meros, 2010).

- Reciprocal Relationship Between Vocabulary and Comprehension – Skilled comprehenders acquire new vocabulary at a higher rate than poor comprehenders. Because a significant portion of vocabulary is learned from context while reading, struggling readers often fall behind in vocabulary growth, which further impairs their comprehension skills (Cain, Lemmon, & Oakhill, 2004; Nation, Snowling, & Clarke, 2007).

- Third-Variable Correlation Hypothesis – Instead of vocabulary directly causing better comprehension, both may be influenced by a third variable, such as general conceptual knowledge or metalinguistic awareness. Nagy (2007) argues that metalinguistic awareness (e.g., morphological and syntactic knowledge) plays a key role in both vocabulary acquisition and reading comprehension.

Moving Beyond Memorization

This may be an unpopular opinion but I strongly believe that rote memorization does have a place in vocabulary building for our students well into secondary grades – and the research supports this. This trick is that it can’t be the only strategy that you use. Here’s what the research says:

Pros:

- Efficient for Initial Vocabulary Acquisition – Rote memorization helps learners acquire a large number of words quickly, which is beneficial in the early stages of second-language learning (Nation, 1982).

- Facilitates Retention Through Repetition – Regular exposure and recall strengthen memory retention, making it easier for learners to recognize words when reading or listening (Pimsleur, 1987).

- Culturally Embedded Learning Strategy – In some educational systems, such as China’s, rote memorization aligns with traditional learning practices and provides familiarity for students (Cortazzi & Jin, 1994).

Cons:

- Lacks Deep Understanding and Application – Memorized words often remain isolated, preventing students from using them effectively in context (Qian, 1996).

- Limited Impact on Comprehension and Fluency – Without contextual learning, students struggle to apply vocabulary in reading and speaking, affecting their overall language proficiency (Oxford & Scarcella, 1994).

- Discourages Critical Thinking and Strategy Use – Over-reliance on memorization may prevent students from developing effective vocabulary-learning strategies, such as using affixes, roots, and contextual inference (O’Malley & Chamot, 1990).

While rote memorization is useful for acquiring foundational vocabulary, it is most effective when combined with strategies that promote deeper language processing.

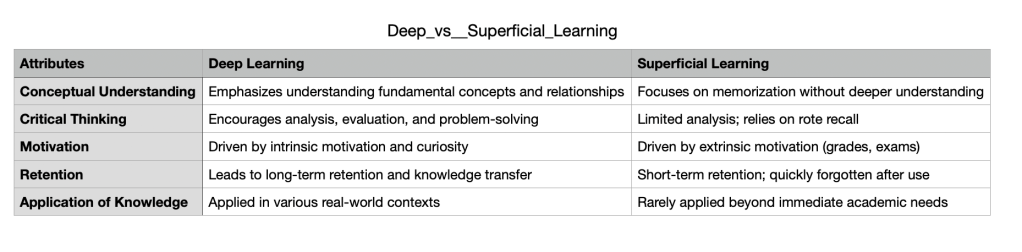

While superficial learning may serve short-term academic goals, deep learning fosters lifelong critical thinking, adaptability, and meaningful application of knowledge. Rote memorization of words lists is ineffective for long-term retention as it belongs to the realm of superficial learning.

Let’s explore strategies for contextual vocabulary learning and active engagement with words belong to the realm of deep learning.

Strategies for Effective Vocabulary Instruction

Teach Words in Context

Mentor Texts

Use mentor texts to explicitly teach reading skills. Here are 8 tips from the article “8 Tips for Teaching With Mentor Texts“.

- Give any vocabulary and definitions up front

- Read the piece out loud or give students time to read on their own in class

- Start off with questions that deal with the content

- When you come back to the text to look at techniques, be as specific as possible, naming sentences or words whenever possible

- Give multiple examples if you want students to try a technique

- Refer back to the mentor texts regularly, in teacher conferences or whole-class lessons or discussions

- Let students see you trying the strategies as well

- Keep in mind that this is likely a new experience for struggling learners

Read-Alouds

Here are three key tips from Morrison & Okonkowski (2010) on using read-alouds to develop vocabulary:

- Teachers should introduce and explain key vocabulary words before, during, and after reading aloud. This includes defining words in student-friendly language, using them in different contexts, and reinforcing them through discussion. Example: Writing target words on chart paper and revisiting them throughout the lesson.

- Rather than relying solely on dictionary definitions, teachers can enhance vocabulary learning by using word walls, word webs, concept maps, and morphological analysis (breaking words into roots, prefixes, and suffixes). These strategies help students make connections between words and develop deeper understanding.

The Power of Word Mapping & Graphic Organizers

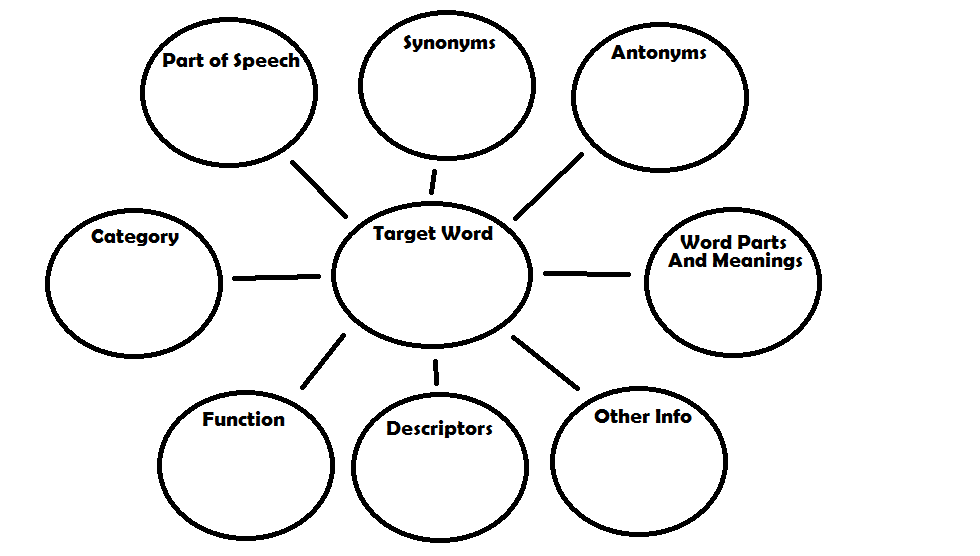

Word Maps

- Choose a Target Word – Select a word students need to understand and expand upon (e.g., “innocuous”).

- Identify Part of Speech – Determine if the word is a noun, verb, adjective, etc. (e.g., adjective).

- Find Synonyms and Antonyms – List words with similar and opposite meanings (e.g., harmless vs. harmful).

- Break Down Word Parts – Identify roots, prefixes, and suffixes (e.g., in- (not) + nocuus (harmful in Latin)).

- Define Category – Classify the word into a broader group (e.g., descriptive words for safety).

- Describe Function – Explain how the word is used in context (e.g., “An innocuous comment won’t offend anyone.”).

- Provide Descriptors – List characteristics or examples (e.g., mild, safe, benign).

- Include Extra Information – Add any additional facts (e.g., “Common in medical and literary contexts”).

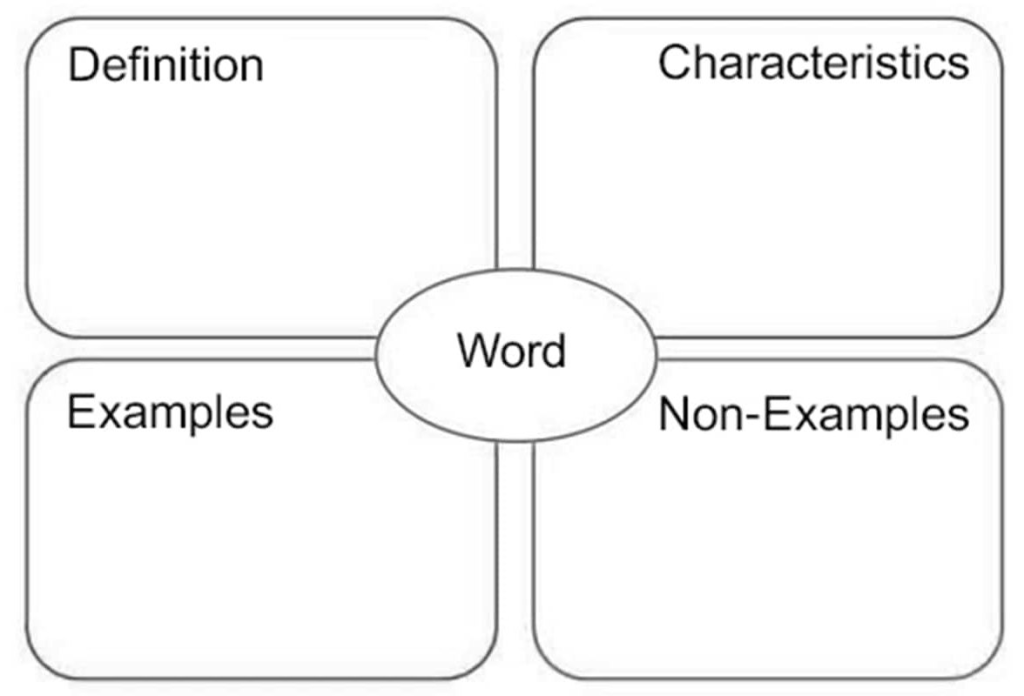

Frayer Model

- Write the word in the center.

- Definition: Students write a student-friendly definition (scaffold if needed).

- Characteristics: List key features of the word.

- Examples: Provide real-world examples.

- Non-examples: List unrelated words or concepts to clarify meaning.

- Compare with a dictionary definition for accuracy.

The Role of Explicit Instruction & Repeated Exposure

Explicit Instruction

The study by Vincy (2020) found that explicit vocabulary instruction and repeated exposure significantly enhance vocabulary retention and reduce the receptive-productive gap, demonstrating that structured teaching methods are more effective than conventional memorization-based approaches.

- explicit vocabulary instruction and repeated exposure significantly improved students’ ability to retain and use new words. In the experimental group, vocabulary retention and production increased by 72%, compared to only 8% in conventional teaching methods

- the research highlighted the gap between receptive and productive vocabulary knowledge, showing that students often recognize words but struggle to use them actively. Explicit teaching methods bridged this gap, helping students transition from passive recognition to active usage of vocabulary

- memorization-based vocabulary learning, common in conventional instruction, leads only to partial recognition, without deep understanding or practical usage. The experimental group, exposed to structured explicit instruction, demonstrated a stronger ability to recall and apply vocabulary in different contexts

Interleaved Spaced Repetition (ISR)

Lafleur (2022) explores Interleaved Spaced Repetition (ISR) in vocabulary learning, demonstrating that combining spaced repetition with task interleaving enhances long-term retention, balances improvements across word meaning, form, and use, and optimizes study efficiency through expanding spacing algorithms.

- ISR significantly improves vocabulary retention compared to traditional spaced repetition. ISR combines interval-based study with task interleaving, promoting both long-term memory retention and deeper learning of vocabulary

- expanding spacing algorithms (e.g., gradually increasing review intervals) helped learners retain words more efficiently while reducing review burden. This allows new words to be introduced without overwhelming learners, enhancing study efficiency (Nakata, 2015, as cited in Lafleur, 2022)

Conclusion

Building strong reading comprehension skills requires more than just recognizing words—it demands deep vocabulary knowledge, critical thinking, and repeated exposure to language in meaningful contexts. Research shows that explicit vocabulary instruction, active reading strategies, and interleaved spaced repetition significantly enhance students’ ability to understand, retain, and apply new words. As educators, we must move beyond isolated memorization and provide students with opportunities to engage with vocabulary through context, discussion, and structured practice.

Try this: Choose one strategy—whether it’s using mentor texts, embedding vocabulary in read-alouds, or implementing spaced repetition techniques—and integrate it into your teaching this week. Observe how your students respond, reflect on their engagement, and adjust as needed. By making small, intentional shifts, we can cultivate lifelong readers and learners who can navigate complex texts with confidence.

Join the Conversation! What strategies have you found most effective for teaching vocabulary and improving reading comprehension in your classroom? Share your thoughts, experiences, or a technique you’d like to try—let’s learn from each other!

References

Cain, K., Lemmon, K., & Oakhill, J. (2004). Individual differences in the inference of word meanings from context: The influence of reading comprehension, vocabulary knowledge, and memory capacity. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(4), 671–681. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.4.671

Cortazzi, M., & Jin, L. X. (1994). Changes in learning English vocabulary in China. In H. Coleman & L. Cameron (Eds.), Changes and language (pp. 153-165). British Association for Applied Linguistics in association with Multilingual Matters.

Lafleur, L. (2022). Interleaved spaced repetition (ISR) in vocabulary learning. ResearchGate. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.13085.38882

Morrison, V. B., & Okonkowski, S. (2010). Using read-alouds to develop vocabulary: Components of a balanced word diet. Michigan Reading Journal, 42(3), Article 5. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/mrj/vol42/iss3/5

Nagy, W. E. (2007). Metalinguistic awareness and the vocabulary-comprehension connection. In R. K. Wagner, A. E. Muse, & K. R. Tannenbaum (Eds.), Vocabulary acquisition: Implications for reading comprehension (pp. 52-77). Guilford Press.

Nation, I. S. P. (1982). Beginning to learn foreign vocabulary: A review of the research. RELC Journal, 13(1), 14-36. https://doi.org/10.1177/003368828201300102

Nation, K. (2009). Reading comprehension and vocabulary: What’s the connection? In R. K. Wagner, C. Schatschneider, & C. Phythian-Sence (Eds.), Beyond decoding: The behavioral and biological foundations of reading comprehension (pp. 176-194). The Guilford Press.

Nation, K., Snowling, M. J., & Clarke, P. (2007). Dissecting the relationship between language skills and learning to read: Semantic and phonological contributions to new vocabulary learning in children with poor reading comprehension. Advances in Speech-Language Pathology, 9(2), 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/14417040701325350

O’Malley, J. M., & Chamot, A. U. (1990). Learning strategies in second language acquisition. Cambridge University Press.

Oxford, R., & Scarcella, R. (1994). Second language vocabulary learning among adults: State of the art in vocabulary instruction. System, 22(2), 231-243. https://doi.org/10.1016/0346-251X(94)90059-0

Pimsleur, P. (1987). A memory schedule. Modern Language Journal, 51(2), 73-75. https://doi.org/10.2307/321812

Qian, D. (1996). ESL vocabulary acquisition: Contextualization and decontextualization. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 53(1), 120-142.

Vasile, C. (2024). Do we still need deep learning? Journal of Educational Sciences & Psychology, 14(1), 1-3. https://doi.org/10.51865/JESP.2024.1.01

Vincy, I. R. (2020). Examining the effect of explicit instruction on vocabulary learning and on receptive-productive gap: An experimental study. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 16(4), 2040-2058. https://doi.org/10.17263/jlls.851033

Wagner, R. K., & Meros, D. (2010). Vocabulary and reading comprehension: Direct, indirect, and reciprocal influences. Focus on Exceptional Children. Retrieved from NIH Public Access.

Leave a comment