The Illusion of Reading Fluency

In a reading conference with one of my Grade 10 students, I asked them to read aloud a short passage from a novel we were reading and analyzing as a class. They pronounced each word correctly, observed the appropriate pauses for punctuation, and generally demonstrated grade-level ready fluency. After giving them a compliment on their read-aloud, I excitedly asked them why the heroine would act out they way she did in the passage the student just read.

Crickets.

Thinking that perhaps I just needed to put my question into context, I asked them what had happened just before the passage they read. There was a quick turn of pages as the student scrambled to quickly scan the text.

And then more crickets.

After some gentle questioning to make sure my conclusions were correct, it became clear that the student demonstrated excellent reading fluency but without the comprehension needed to make predictions, inferences, or analytical commentary.

The reality is that despite being able to read fluently, too many students don’t understand what they just read.

- Why does this happen?

- What are the underlying problems?

Myths That Persist in Secondary Schools

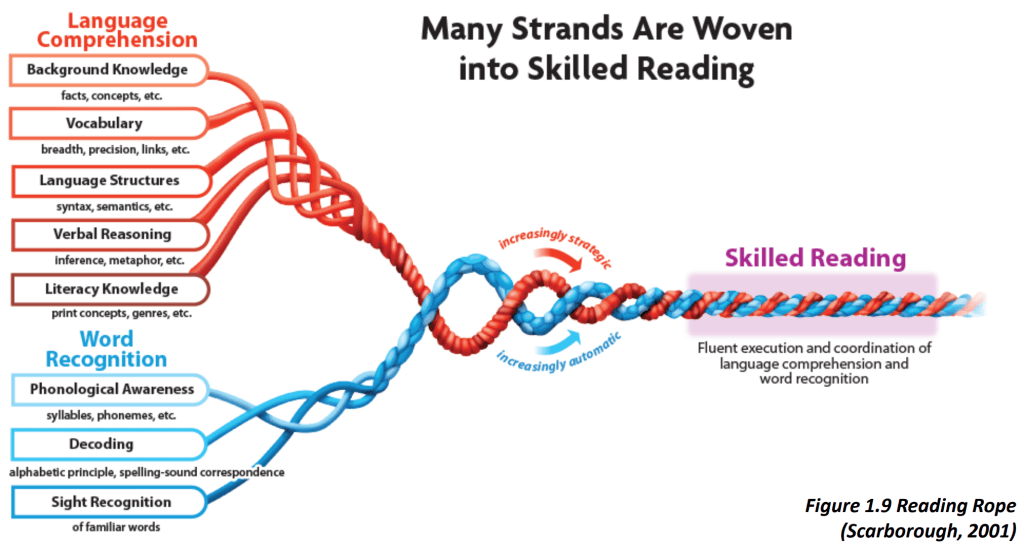

At the elementary level, the focus is on sight recognition of familiar words, decoding, and phonological awareness to achieve consistent word recognition. Many secondary teachers assume students already “know how to read” by middle and high school. At this level, the focus shifts to content knowledge and away from literacy skills, putting struggling readers at risk. Often, they develop compensatory strategies such as memorization or picking up on context clues that may mask their difficulties.

Reading is a complex skill that continues developing beyond elementary and into middle and high school. Even proficient-looking readers may struggle with deeper comprehension.

Debunking the Biggest Myths About Reading in Secondary Schools

Myth #1: “If they can read aloud fluently, they understand it.”

Reading fluency does not equal comprehension. A student can sound fluent but miss the meaning.

Scarborough’s Reading Rope (2001) reveals that reading comprehension requires literacy knowledge, verbal reasoning, language structures, vocabulary, and background knowledge – not just word recognition. If a student is struggling with understanding what they have just read, they are most likely missing one of the strands of the reading rope related to language comprehension.

Myth #2: “Middle and high school students don’t need reading instruction anymore.”

Continuing to develop strong vocabulary banks and broadening their vocabulary knowledge will help students comprehend more of what they read; this is especially true as texts become more complex in the middle and high school grades (Sinatra, Zygouris-Coe, and Dasinger 2012).

This is also especially true as middle school and high school content-area reading becomes more complex in subjects like science, history, and math. In fact, studies show that older students benefit from explicit instruction in vocabulary, morphology, and text structure (Hennenfent et al., 2022; Hall-Mills and Marante, 2022) ).

Myth #3: “They should have learned reading strategies in elementary school.”

Many students never mastered comprehension strategies and, as previously discussed, texts get more complex in secondary school. This increase in text complexity demands new strategies for comprehension such as activating, searching-selecting, and visualizing-organizing.

What the Science of Reading Reveals About Adolescent Literacy

Word recognition and decoding still matter. Older students struggling with comprehension may have gaps in foundational skills; this may even be something as foundational as phonological and phonemic awareness.

Background knowledge is crucial. Without it, students struggle to make meaning, even with strong reading skills. Understanding the social issues prevalent at the time J.P Priestly wrote “An Inspector Calls” will help students understand character motivations as well as the relevance of social issues being explored. Understanding the concept of “traditional gender norms” will help students analyze the significance of the website “The Father Hood” which explores the changing role of fathers from the perspective of men.

Explicit instruction is important. Students need to be taught comprehension strategies, grammar usage and mechanics, content vocabulary, and other reading skills across all subjects.

How Teachers Can Identify Struggling Readers in Secondary School

Here are some signs to look for as taken from Collaborative Classroom:

- Frequent Misunderstandings and Requests for Clarification

- Avoidance of Reading Tasks and Difficulty with Complex Texts

- Slow Reading Pace

- Performance on Reading Comprehension Tests

- Limited Vocabulary Use

- Difficulty Summarizing Texts and Making Inferences

- Inconsistent Homework Quality and Reliance on Peers

- Low Engagement

Here are some quick classroom strategies:

Use Think-Alouds to model reading comprehension strategies.

Provide scaffolding for difficult texts (e.g., chunking, guiding questions).

Teach vocabulary explicitly—not just subject content.

Provide background knowledge to deepen comprehension.

Final Thoughts: Rethinking Reading in Secondary Schools

Reading is not just an elementary school skill – it’s a lifelong process and we have a responsibility to guide students through the various stages of their reading journey. Teachers in every subject can support this literacy journey. Science-backed strategies can help struggling readers succeed in middle and high school.

Comment below: What are the biggest reading challenges you’ve seen in your classroom?

References

Hall-Mills, S. S., & Marante, L. M. (2022). Explicit Text Structure Instruction Supports Expository Text Comprehension for Adolescents With Learning Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Learning Disability Quarterly, 45(1), 55-68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731948720906490

Hennenfent, L., Johnson, L. J., Novelli, C., & Sharkey, E. (2022). Intensive intervention practice guide: Explicit morphology instruction to improve overall literacy skills in secondary students (ED628200). Office of Special Education Programs, U.S. Department of Education. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED628200.pdf

Keisler, L. (2022). What the science of reading says: Literacy strategies for secondary grades. Shell Education.

Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. In S. B. Neuman & D. K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research (pp. 97–110). Guilford Press.

Leave a comment